Where does Africa end?: Bilad il Asmar - An opening conversation with Sanyika Bryant

It is my honor to introduce you all to a very special person today and to initiate the first official post of our SWANA Ancestral Medicine Hub column, “Where does Africa end?: Bilad il Asmar”. This column is dedicated to an exploration of the historical, cosmological, political, and cultural relationships between Africa and South West Asia (aka. SWA, colonially referred to as “the Middle East”, also often categorized as SWANA- South West Asia and North Africa). Sanyika Bryant is our very honored guest writer of this column, where he will be sharing some of his long cultivated wisdom and knowledge with us. You can follow Sanyika’s sharing on the part of the Hub titled “

Where does Africa end?: Bilad al Asmar

”. Also check out his Black-Arab Facebook album for a lot more info and images related to this topic. It is beautiful.

Sanyika is a gifted New Afrikan historian, political organizer, and someone who is deeply interested in the Mysteries. I have been very fortunate to build with him over the past 11 years as we have embarked on parallel and intersecting journeys of ancestral healing and re-membrance. Sanyika is both one of my best friends, and one of my closest spiritual kin and peer-teachers, whose expansive knowledge and consistent witness and reflection has profoundly supported and influenced my own ancestral re-membering since we met in 2006. This column is an elaboration on one of the many topics that Sanyika and I have been building on and reflecting about this past decade, as we have explored and sought to deepen understanding about ourselves and the relationships between our respective and overlapping ancestral regions and diasporas. Sanyika is truly one of the most knowledgable people I have met in the arena of ancestral traditional practice and cosmologies, and the historical relationships, lived experiences, and migrations of our globe’s original people, especially those of Africa and the SWANA region. It is with deep honor and gratitude that I share this conversation with you all today, a sneak peak into Sanyika’s extensive knowledge and some of the themes of our relationship which he will be elaborating about on our hub.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Layla: Hi Sanyika. I am really excited to uplift some of the incredible research you have been doing about our peoples and ancestors and their intersections, things that you and I have been deepening about in private for over a decade now! Thank you so much for your dedication, and you generously sharing with us. To start, can you share with us a little bit about yourself, who you are, and your own ancestors/lineage?

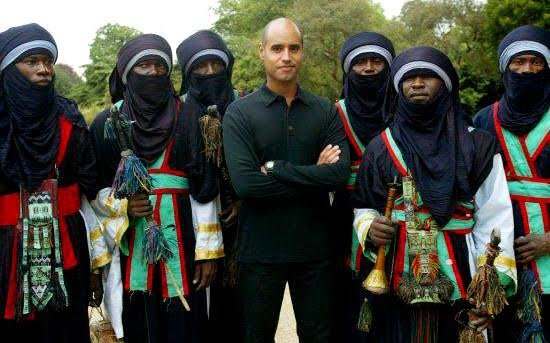

Sanyika: So firstly I'd like to start off with the meaning of my name. My name means the Gatherer of his people. It's really been what's guided me through my life. I consider it my mission and purpose. I'm also the oldest of my parents 6 children. I've been really interested in history and cosmology, the creation stories that reveal a people's understanding of their origins and their place in the universe. Through my love of history and cosmology I’ve been able to find out a bit about my ancestors and their relationships. On my mother's side of the family we are partly Igbo from southeast Nigeria. On my dad's side I'm partly Fulani or Fulbe. They are one of the largest nomadic nations on the planet and live in more than 19 African countries. I've been been blessed to find this information as many people who are descended from enslaved Africans don't have this information. I'm able to trace my family on my mom's side back to the 1760s and on my dad's side to the 1830s.

Layla: Beautiful and inspiring! Much gratitude and respect to you, your parents, and your ancestors for anchoring and uplifting your purpose and path with such profound clarity. Undoubtedly, there is a LOT to talk about and share around how you have navigated this process of discovering who your ancestors are and how others amongst us who are seeking that connection might go about doing so if we don't have that information readily available to us. As you know, that is a large objective of this Hub and the نجمع جذورنا - reGather our Ancestors project that houses it. Do you have any initial thoughts or ideas/advice to share with us about this journey to reconnect to our lineages? What are a few initial steps you might suggest to people doing this work to re-member our ancestors and their original ways?

Sanyika: It really depends. Each person will have a different process. It is a very personal journey. If one has access to grandparents and other elders, that's an obvious place to start. Asking questions about food, games, what they remember about their own grandparents, their childhood, stories their parents told about theirs are all good places to start. I also have been blessed with the knowledge of how to look into history for relationships. Being able to place your family story within a broader historical context can open up a lot of doors. Also, I'd advise people to think about what they are leaving behind to help their descendants find them. There are old traditions among New Afrikans of writing the known family history in a family bible for example. These sorts of family records are invaluable and sacred. Knowing how hard it is for so many of us to piece our stories together, we should take special care to do whatever is in our power to make this task easier for our children and grandchildren. Personally I’ve used a mix of family stories, census records, and even rituals to open the way for me.

Layla: Yes! I know that your gift with placing things historically has created for a really dynamic process in my own relationship with you, always supporting me in deepening and filling pieces of the puzzle as we have both navigated these parallel processes of ancestral re-membering with our own unique approaches and offerings to each others unfolding. I am looking forward to more of those historical pieces coming into the broader community via your archives and sharing on its way, especially knowing how valuable and profound they have been for me, and how suppressed and misrepresented so much of this knowledge is. I appreciate you drawing consciousness to our responsibility to somehow record and pass down our re-memberings as we embark on this work as well- a really critical piece, especially in age where so much of what is left of our ancient knowledge is actively under attack or being neglected into extinction.Can you tell us more about what has inspired your attention to the SWANA region and its traditions and peoples? Why is this particular relationship and region of interest and importance to you?

Sanyika: It initially started when I was about 3 years old when my father took me to an exhibit on ancient Egypt that the Oriental Institute of Chicago was hosting. When I saw the actual bodies of these ancestors and some of their art and religious artifacts I knew it would be part of my life forever. I immediately began to question why the very dark skinned mummies I had seen looked nothing like the white people in the ten commandments movie that we'd watch every year or the white people in the Jehovah's Witness propaganda my grandmother was always showing us. That triggered my initial curiosity. After that other influences were really religious curiosity. Like a great many New Afrikans, I wanted to get deeper into the cultural context of the Abrahamic traditions and really sort of find myself in them. After a while I saw that what I was connecting to the most out of these traditions were their mystic sides; the gnostic, kabbalistic, and Sufi teachings. It became clear to me after having looked at different cosmologies, that some of what I was connecting to in these traditions were very ancient remnants of mystery systems that for a multitude of reasons were able to survive tumultuous cultural and political shifts.

Another reason why this relationship is important to me is because of the political relationship between our folks. The Black Liberation Movement has historically stood in support of the liberation of Palestine from Zionist Israel. We have had a joint struggle against the Zionists for decades. Zionists are responsible for destroying SNCC (The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee). They gave nuclear weapons to Apartheid South Africa and spied on the international Anti-Apartheid movement on their behalf. We have a common enemy and our liberation movements have a lot to learn from each other. I am a Pan-Africanist (it’s even built into my name) and in my view, Arabia has always been part of the African world. Be it from the migration of different tribes out of what’s currently considered to be Africa into what’s currently considered to be Arabia and vice versa over several millennia, the cultural interchange of food, music and dance, and the sharing of cosmological systems, there has always been a link. We are often times literally family, and like in every family, there will be love and harm done within them. I look at what’s going on today in the world with the continued imperialist violations happening in Africa and Arabia and how the fallout of these crimes and crises is impacting the whole African and Arabian region. What’s happening in Syria is very similar to what’s been going on in the Congo as far as the massive refugee crisis it’s created as well as the lack of organized response to give political support to the grassroots forces of those countries who are fighting for their survival and the basic right to exist on the planet.

The relationship runs deep. Even on just a personal level, you’ve been one of my best friends for over a decade and there’s been so much weaving in our lives. We’ve shared soooo many stories together. We’ve been there through political and personal tragedies, we kick it with each other’s siblings, and I even have deep dreams about your father where more of his Canaanite side comes out. The relationship expresses itself through my love of Gnawa music, the way olives and pomegranates are my favorites fruits, my favorite Fairouz song being Zahrat al Madaan , and even the way my father felt that it was important to take me to the mosque for the exposure.

Layla:

Yes, the love and learning has certainly been deep between us and our family’s, hasn’t it? And the sense of kinship spiritually, culturally, and politically has certainly moved in both directions. Whether it’s learning tarot spreads passed down from my aunty while we hang with the siblings, geeking out on Yoruba, Egyptian, or Sumerian cosmology together, strategizing around the “right of return” from Hurricane Katrina to Palestine, or the freedom of our political prisoners, or divining coffee grinds and ancestral dreams at our favorite Ethiopian spot, the reflections have always led to something profound.

I think your framing of “Arabia” beckons a question for clarity around where specifically you are referring to when you say that? What current day countries entail what you refer to as “Arabia”? Where does “Arabia” begin and end as you speak of it here?

Sanyika:

That is a good question. I’m speaking about Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Bahrain, Qatar, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine. Perhaps there are issues with the term itself because it includes peoples who aren’t “Arab” historically and who have different identities. It’s an interesting question. Where does Arabia end and begin? Do we include Libya, Egypt, Morocco, Algeria, Sudan and Tunisia? Are we talking about a sphere of cultural influence? Are we talking linguistic regions? Are we talking about the lands where the Arabs became a unique people? In any case, there is a historical and current exchange happening here. There is also the question of if these areas are to be considered Arabia, when did they become part of Arabia? For example, if you include Iraq as part of Arabia it likely only makes sense to do so if you are talking about Iraq after the fall of the Sasanian Empire in 651 c.e.

The other question is where does Africa end? Europeans arbitrarily decided that Africa ends at the Red Sea, yet this notion goes against the history and geography of the region. They did this for their own geopolitical and imperialist interests. To combat this, the term “Afrabia” has been used by some historians and anthropologists to acknowledge the ancient historical, cultural, and geographical relationship between Africa and Arabia. It’s a term that combats Eurocentric geopolitical definitions of the region.

Layla:

Thanks for clarifying and highlighting that important piece of history regarding “Afrabia”. In and of itself, “Arabia” has always been an incredibly ethnically, culturally, and racially diverse region despite the current ways that it is often characterized into a monolithic (and largely colonial) identity. You mentioned above that not all of the people living in “Arabia” are or were “Arabs”. Can you elaborate for us a bit about what that means and what other peoples you are referring to when you say that? Are there any of these non-Arab peoples of Arabia who have struck a particular interest or connection to you? Can you tell us a bit about why and who they are?

Sanyika:

Certainly. Among the people that I am referring to are the Canaanites. The Canaanites are some of the people who represent a direct connection between Africa and the Levant region in particular. It is well known, despite the attempts of European propagandists to say otherwise, that the Canaanites were an African people. Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria were among their lands but before then, they had origins in the Sudan. You yourself come from a Canaanite lineage. There is still an ancient Canaanite people known as the Qemant who live in Ethiopia. The Qemant are currently in danger of having their entire culture wiped out because of social pressures to assimilate into the Amhara and Tigray peoples. They are among some of the last people that have preserved some of the Pre-Abrahamic Canaanite traditions. Their tradition has shifted and changed over the millennia just like any other tradition but it still maintains its ancient roots. These roots are very “African” in character, particularly in the way they revere their ancestors. It is important to remember that the Canaanites were the founders of the Phoenician empire and that there were two Phoenician kingdoms, one in the Levant centered in Tyre, Lebanon and the other was Carthage (or Khart Hadasht) in what is now Tunisia. The Berbers or the Tuareg peoples are the descendants of these Canaanites. “Now the real fact, the fact which dispenses with all hypothesis, is this: the Berbers are the children of Canaan, the son of Ham, son of Noah. Their grandfather was named Mazyh...the Philistines children of Casluhim son of Misraim son of Ham were their relations...." Ibn Khaldun, 15th century Andalusian North African.

I connect to this history because of my Fulani lineage. The Fulani and the Berbers are very closely related people. Other groups among the Berbers were the Soninke who were the founders of the ancient Ghana Empire (in Mauritania, Mali and Senegal) and the Songhai (Isuwaghen/Azouagha) who founded the Songhai empire, a later empire that was also located in Mauritania, Mali and Senegal. This is a direct connection between people from West Africa, North Africa, and East Africa to Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria. "The Azuagos are one of the peoples who spilled into Berberia and Numidia, most of whom are shepherds; others are weavers of cloth or cowherds. A poor people who live in and around the hills and in caves, mostly tributaries of the local kings or of the Arabs. These peoples (according to African authors) originally came from Phoenicia, and were called Moors or Morophoros; they were thrown out of the the land of Joshua, son of Nau, who lived with the Egyptians, passing to Libya and afterward founding the famous city of Carthage, 1278 years before the birth of our Lord Jesus Christ, who was 3929 years after the creation of our world. And according to Ibni Al Raquiq, for many years they lived in this city, a great stone city with a fountain, saying: 'We are the people who fled the presence of the thief of Joshua, son of Nau.' When these people came to Africa, they had already ruled it, Asclepios and Heracles, and also ruled Spain, 1693 years before Christ. After that, Carthage being destroyed for the first time, before Dido re-established it, some of these peoples passed through western Berberia, with Annone, their captain. They established the Libyan cities, Phoenician cities, where they lived when the Romans came to Africa, calling it Mauretania, named for the valley dwellers called Maurophoros." - Luis del Marmol Caravajal, Granada, 1573

Layla:

Welcome to encyclopedia Sanyika Bryant, y’all. Welcome to a glimpse into the brilliance and knowledge that I am so very inspired he will be sharing and elaborating on in this Hub. Thanks for sharing this history and your knowledge with us. It’s true what you said, Sanyika. This relationship to African-ness and Canaanite lineage specifically was highlighted to me repeatedly during my Homeward Healing journeys through the SWANA region this past year too. When I was in the Bedouin community of the Sinai region of Egypt, a spiritual elder, herbalist, and historian shared with me that the ancestry of his own family is actually Canaanite too (it came as a surprise to me since I had always known the Bedouin to be from the Arab Gulf originally, but he explained that there are several different Bedouin tribes and theirs is Canaanite in origin, many of their traditional practices still reflecting that). And when I was in the Nubian region of Aswan in Upper Egypt, a historian and elder I interviewed there also reiterated to me that the Canaanite ancestry of my own region originally were a tribe of Nubia, as you mentioned from the Sudan. He explained that Nubia was comprised of many tribes dwelling across the Nile Valley, from Ethiopia and Eritrea through Sudan and Egypt, and that the Canaanites at some point migrated north from that region. Some of these themes of African origins also came up during my short time along the Arab Gulf on the southern coast of Iran, particularly when learning from people about the origins of some of the traditional music, folk medicine, ceremonial and traditional practices such as the Zar, which I was taught also originates in Ethiopia and Eritrea though is most strongly practiced in the Arab Gulf and parts of North Africa and the rest of “Arabia”.

This relationship can, however, be a delicate topic to navigate in a world where Blackness is both demonized and rejected, and objectified and appropriated simultaneously, where African ancestry in the “Arabian” places and lineages we are discussing often does not match up with a Black experience contemporarily and all that it entails in this White Supremacist world, and where in the SWANA region, there is unfortunately still a great deal of anti-Black racism despite the African origins many of our peoples actually come from. This also includes the long histories of enslavement of Africans in the Arabian Gulf areas. This is without me even getting into the contemporary practices throughout all parts of what you call “Arabia” involving the very cheap contracting of foreign workers from mostly East Africa, South & East Asia, in a way that disturbingly mimics slavery and further contributes to a culture of racism in the modern relations in the region.

On the other end, it is a controversial topic in the “Arab” community where some worry about the fracturing of our already vulnerable regional unity when people in any way choose not to identify with their Arabness, and where the insistence to maintain ethnic or ancestral identity that precedes our Arabness has been at times used by reactionary political forces to seed divisions and fracture geopolitical unity, making the region vulnerable to Western imperialist and sectarian agendas (such as the Phalangists of Lebanon exploiting the notion of the “Phoenician” origins of Maronites to separate themselves from Muslim and “Arab” neighbors to advance their own political agendas. In truth, most of whom they were trying to distinguish themselves from are also known descendants of Phoenicians/Canaanites and it was just a sectarian political ploy). At the same time, the insistence of ethnic and religious minorities in the region to maintain their pre-Arab and pre-Islamic identities has been rooted for many of these communities in a struggle for self-preservation and a resistance to colonial conversion in a climate that doesn’t always recognize them, protect them, or respect their existence and self-determination despite their indigeneity in the region, creating profound and very real tensions for those who refuse to assimilate (some obvious examples being the Chaldeans, the Nubians, and the Kurds, though even many of the populations that have been assimilated to “Arab” identity have faced these histories of cultural erasure, whether or not it is even recalled- particularly across the Levant and North Africa). It is hard to have these conversations without acknowledging the profound influence of all these dynamics.

All to say, it is an incredibly complex and nuanced history and conversation. And given all these complexities, I am imagining that this conversation may be a point of tension, resistance, and misunderstanding amongst some members of both our communities, while providing long sought answers and resonance to others. Any thoughts or reflections about that as we enter this collaboration and make some of these conversations we have been having for the past decade public?

Sanyika:

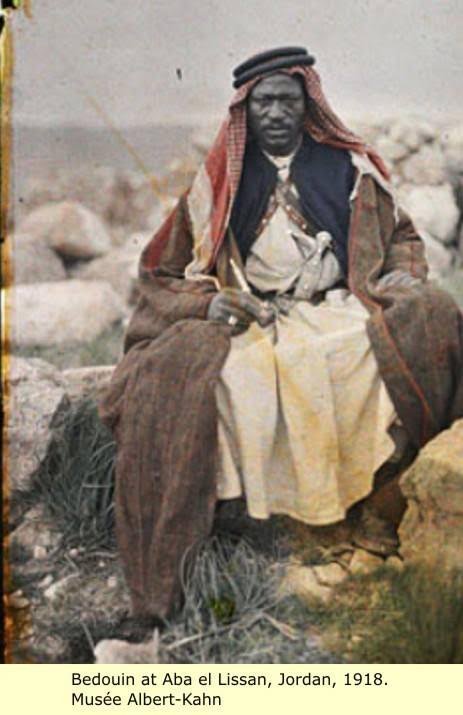

Complexity means there will be different perspectives. In my opinion everyone indigenous to that region is an African whether they are “Black” or not. It makes no sense to separate it out. The Slavery issue is a deep one and for my people in the diaspora it brings up a lot of pain for sure. But there has been a lot of misrepresentation of this history. Yes there was an Arab led slave trade that captured people (mostly women and children) in East Africa, and yet at the beginning this slave trade was mostly done by people who’d be considered Black against other people who are considered Black. In the early period most of the slaves were actually coming from Eurasia, a lot of whom were Slavs (which is where the word slave is derived from in the first place). When The Arabs were fighting against Byzantium (the Eastern Roman Empire) and conquered Egypt, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria, the vast majority of those Arab conquerors would be considered Black today. A lot of the people who were conquered hadn’t become Arabs yet, a major exception being the Ghassanid Kingdom of Arabs from the Azd tribe who migrated from Yemen to Syria. This is not to say that there weren’t a lot of Arabs there, there were. But the majority of people in that area were not identifying as Arabs until after the Umayyads conquered the region.

It is also important to note that when it comes to West Africa and East Africa, conversion to Islam was mostly peaceful. If the same wars of conquest had been engaged in by the Arabs in those regions it is likely that you’d have “Arab” states in West Africa and East Africa. In the West and East African context, the spread of Islam was peaceful. The Arabs didn’t have a colonial relationship in these areas when they began to spread Islam. The colonial relationships (particularly with East Africa) happened at a later date, (particularly with control of Zanzibar by the Sultanate of Oman). The relationship certainly wasn’t rosey all the time. The East African Slave trade was brutal and has had an impact on the whole continent, becoming the cause for numerous wars and the loss of a lot of culture. There is also the history of rebellion like the Zanj Slave Rebellion in Basra, Iraq 869-883. There is so much to get into. That's why there's a blog!

Layla:

Whew. Haha. Yes, we thankfully have a LOT of space to really honor and deepen with this knowledge through our Hub. This is just the first of it, and you are already touching on some deep roots and flushing out a lot of really tender pieces and contentious histories that so many people in both of our communities I think have been trying to make sense of in different ways (and perhaps at the same time, not enough of us). And you are barely even touching the iceberg yet! It is so critical and rare to have this conversation with all these multiple dimensions regarded and held together simultaneously. For myself as a Shami person (Bilad il Sham is the Arabic title for the Levant- Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, Jordan), I feel strongly about the importance of acknowledging the completeness of this history, all the blood and stories and lands that my lineage, body, and spirit carries, and especially acknowledging the very large percentage of ancestral heritage that has been forcibly erased over generations of conquering and colonization by both local and European empires and the cultures, languages, religions, and practices they have insisted. I strive to honor and learn from the understandings of my original ancestors, which are not nearly as accessible as I wish them to be, and I think that paying homage to my/our African ancestors is a deeply important piece of that healing and decolonial work- especially in a global climate where Blackness and Africanness is criminalized, terrorized, and disregarded constantly, despite the fact that so many of our ancestral origins and current blessings are directly built from it, particularly as “Arabians” (or should I say, "Afrabians"). So, I thank you for sharing your perspective and wisdom about our ancestors and regions to bring so much of this history to the light of day where we can all see it and take a real look at where we come from and who our ancestors are and ultimately, the wisdom and medicine within these relationships that can help us ALL re-member and get free respectively and in more authentic kinship and support. I know you have a lot of deeper sharing on the way about all of these pieces, including us coming to a deeper understanding around the roots, origins, and particularities of Anti-Black racism in the SWANA region. That will be incredibly important for contending with and committing to more effective ways to understand and address the oppressive racial and socio-political dynamics currently at work in and beyond the SWANA region and through our relationships in the diaspora, and I know I am not the only one looking forward to diving deeper into that piece soon.

Can you tell us a bit about the name of the column and it’s significance and meaning?

Sanyika:

When we were brainstorming the name for the column, we wanted something that spoke to the question of where does Africa end and where does Arabia begin? We wanted something that spoke to that specific relationship. Bilad il Asmar means the land of darkness in Arabic. It speaks to the connection of the SWANA region with the rest of Africa through ancestral and cultural connections.

Layla:

Awesome. There is so much more to build on here, but for now, I’d like to thank you for sharing all this and for the sharing yet on its way, and also to honor you for your dedication and gifts and for archiving all this knowledge so you could share it with us for the betterment of our communities. Any last reflections you’d like to leave us with?

Sanyika:

Thank you for this opportunity, Layla. I’m looking forward to contributing to this work. This dialogue is especially important right now. If folks want to reach me I can be contacted at sanyika.unity@gmail.com. We are only really scratching the surface here. I hope to really share some of what I’ve found in my research and the conclusions that I’ve made because of it. I hope that it provides some level of inspiration for more of our people to come together in our respective homelands and diasporas.

One thing I want to make sure to address before we finish is the fact that Black African people are indeed indigenous to the entire Arabian Peninsula and aren’t there primarily because of slavery or recent migrations. It is very important to take into account the fact that the Arabian Peninsula was the very first place human beings went to when they left Africa. It is known through the science of archaeogenetics, that the African ancestral group that every human population with roots outside of Africa are descended from, migrated out of Africa into Arabia about 70,000 years ago. They didn’t all leave. This means that for more than 70,000 years there have been Black people in Arabia. It hardly gets more indigenous than that. To claim that Black people are in Arabia primarily because of slavery or modern economic driven migration erases tens of thousands of years of history in the region and the very long connection Arabia has with the rest of Africa. This region represents the homeland of the very first African Diaspora.

Layla: “This region represents the homeland of the very first African Diaspora”. That is so deep to reflect on. Thank you and likewise, Sanyika. I am so excited and honored that this sharing is finally happening publicly, and like you, hope that it builds towards greater unity between our people. In honor of our ancestors and our generations still on their way, may this dialogue be medicine towards our liberation(s), and a deep healing balm on the colonial wounds and amnesia that have been in our way, waking up the wisdom our ancestors have woven deep in our bones to help us thrive and overcome in even the most challenging of circumstances. These things have plagued and divided us for far too long. Deeply honored to host and support this critical sharing, khayeh (brother).

**Please note that ALL of this writing is being offered without funding and as a labor of love to our peoples. Let’s uplift our brother Sanyika’s generous and critical work, which is comprised of years of dedicated education, writing, and research starting since he was just 5 years old! Donations can be sent directly to Sanyika at this link, and/or if you would like to contribute to the continued offerings of the Hub more generally, you can donate here. Another very important and accessible way to support is to PLEASE SHARE and help us circulate these contributions, so they may reach all the eyes and hearts who need them most. Thank you in advance!----------

Layla Kristy Feghali is the creator of River Rose Re-membrance, the home of نجمع جذورنا –reGather our Ancestors Program and the SWANA Ancestral Medicine HUB. She is a plantcestral educator, aspiring ethnobotanist, & apprentice of ancestral healing traditions. Her work is dedicated to the decolonization, healing, and re-membrance of the original teachings and medicine of our indigenous ancestors, with a particular focus on the SWANA region.