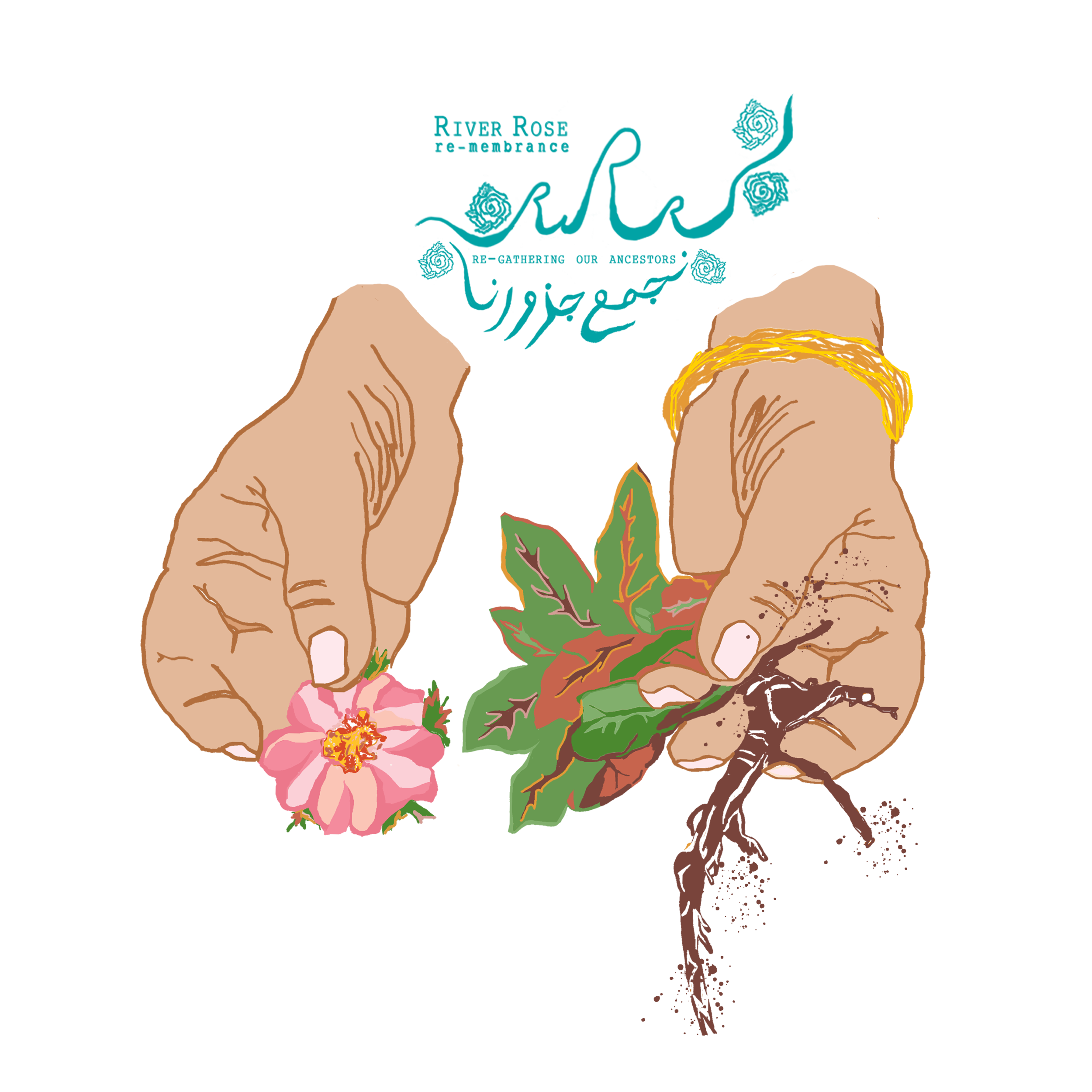

Arasında (In Between)

By Ilhan Dost

As a child I understood, on some level, that I was living between worlds.

I was born and raised in suburban Central Florida, on Seminole land - palmetto scrub and cypress stands razed to make way for cookie cutter housing, strip malls, theme parks, parking lots. Like my parents, my life was governed by the rhythm of the work day - I was dropped off to a childcare center before school started and waited in an after school program to be picked up again. We would close our evening with cheap food and the blue glow of television. Our lives were an automatic pantomime of a nuclear family with the ambitious dreams of an immigrant father and a rural working class mother. Early childhood trips to Anatolian Turkey broke this routine and revealed another dimension of land, language, culture, and ultimately, of longing.

In my first memory of descending from the clouds to İstanbul, my child senses registered a certain weight to the air, an almost palpable heaviness, as if the atmosphere were saturated by milenia of dust, blood, bones, tides of movement and scars of war. For me, Turkey was a place where I was delighted by the ubiquitous presence of goats, where the haunting ezan, call to prayer, would shock me out of sleep, where layers of mystery, or perhaps danger, seemed to be waiting around the corner for incautious children.

Indeed, there did not seem to be as much cushioning against the cycles of life and death as I had experienced in the US. I would soon learn that goats were particularly prevalent on this trip because we were approaching Kurban Bayram (Eid Al Adha). Suddenly goats, creatures I had only encountered in American petting zoos, were tied in front of the apartment building which housed my babaanne and halalar (paternal grandmother and paternal aunts). My cousins and I befriended our new pets. We marveled at the shape of their irises and laughed as their agile mouths nibbled the leaves of roses from our hands.

I awoke on bayram morning, oblivious, eager to peak at our goats from the window, to be utterly shocked at the sight of blood outside, evidence of the ritual covenant of sacrifice. I could not understand the meaning behind this abrupt butchery, nor could I understand how I had not been shielded from the sight of so much blood and the horned skulls of my playmates on the sidewalk, by my adult relatives. This was not Disney.

Yes, death did not seem as easy to conceal in this land, and yet it was still a world that was overwhelmingly full of life. The streets were full of people and movement, of animals, of noise, of the rhythms of commerce and prayer, in a way which made the lonesome suburbs I called home seem like the land of the dead. The homes were full of warmth, of the fat arms of extended family, of many cousins waiting to show me the local secret places, games and tricks they knew. The streets themselves seemed to erupt with children to play with. As a shy, only child all of this nourished me with a sense of being and belonging like nothing else I had known.

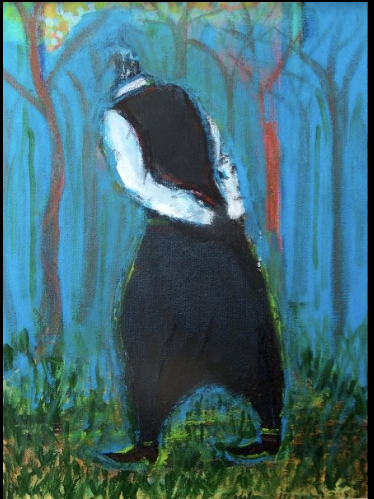

Bir varmış, bir yokmuş - Once there was, once there wasn't - (2009) Acrylic painting on canvas

Years later, in my teens, I spent most school vacations on trips to Çukurova, South-central Anatolia. I compared myself to Persephonewho was forced to split her time between the underworld and the world of the living. I spent over half of the year in a numbed stasis, going through the motions of school and work. With a pale complexion favoring my mother’s German settler ancestry, I had no clear sense of identity outside of whiteness in the US. So many dormant parts of myself seemed only to come alive under the Mediterranean sun, in the embrace of kin, breathing in the air, swimming in the water, eating the foods - all permeated with the elements and the essence of my ancestors.

Here I would sing with my cousins, out-dance relatives at weddings, wear şalvar, eat mumbar, always trying to demonstrate my authenticity and dedication to heritage. My aunts would jokingly suggest that I was “more Turkish” than their own children and other nieces and nephews who sought out Western styles. I relished their suggestion. More Turkish, perhaps, with the exception of my poor capacity to actually speak Turkish, an ongoing obstacle and source of pain.

When I began kindergarten my English skills had gone dormant. It was immediately after a summer trip to Turkey, where I had been completely immersed in the world of family. I tried to speak to other children at school and was horrified that Turkish words came out. My mother did not speak any Turkish beyond a few polite phrases. This inability to speak English disturbed me. It was like gasping for air, grasping to be understood. I began crying whenever my father tried to speak Turkish with me. Unfortunately, he lacked the patience to help me overcome my psychological hang-ups and gave up on trying to instill his language in me. His frustration felt like my fault, as did this linguistic choice I made as a 5 year old, which haunts me still in the kırık or broken Turkish I speak today. Perhaps this was the beginning of my alienation from my father’s culture and a denial of my origins.

I knew of no other Turkish children at my school or in my neighborhood. Besides an occasional Turkish community picnic, or a rare visit with Turkish acquaintances, I had no exposure to Turkish or SWANA culture in the US beyond my father. What exposure I did have often disturbed me, as when a young Turkish-American boy locked me in his bedroom and demanded I marry him, while our parents sipped tea downstairs. Lacking community, I had no real sense of who I was in the context of US minority populations.

As I entered my pre-teen and teenage years, I was increasingly embarrassed of my heritage. I just wanted to fit in, which meant, I just wanted to be a “normal” kid - all-American, white - with a name the teachers did not fumble, with an all-American dad to match. My father could see this in me, and he was angry and ashamed of his disrespectful Amerikalı child. He did not know how to support me. In hindsight, I doubt he knew how to support himself as the parent of a mixed child, let alone as an oppressed and assimilated minority in his native land. How could I be proud of who I was when it was not even clear to me who he was?

It was not until I was 15 that I even understood that my father’s family were of an Arab minority. How often had dad proudly called himself a Turk? Much later I would learn that we are Arap Alevi or Alawite, with origins in Latakya, Syria. My father too had been ashamed of his identity in a Sunni and staunchly Turkcentric society. He too had forgotten much of the Arabic his elders had spoken to him as a child. He too made choices to fit in and belong in Turkey.

It must have pained him to see this same tendency in his child - the urge to conform, to forget, to belong. Yet, he was the first in his family to leave not only hometown, but nation behind, and to love and have a child outside of the arranged marriages of his culture. He would look into my eyes and tell me how he never imagined that he would have a “green eyed child,” but there I was, a reflection of all of my ancestors, full of confusion and questions, which I carry still.

My father Cahit, from the Arabic جاهد , the man who struggles, died in 2001.Before his death, we had traveled together to Turkey, to his hometown, Adana, where he was so loved, so respected - a respect I could never match to his liking as an argumentative teen. On the day that we departed for the airport to return to the US, the slightest rain fell, for only a moment - so rare in the summer, like a blessing of tears. It was as though his city knew that this prodigal son would never again walk the dusty streets which had raised him. His city revealed the open secret of his dying, that which we were unable to admit, as we watched his body atrophy and yellow with jaundice, succumbing to undiagnosed pancreatic cancer. A few weeks later he returned in a metal box, to be cleaned, wrapped in a shroud and laid into the soil with his ancestors.

Anneciğime - To my dear mother - (1960s?) BW Photo postcard of my father addressed to his mother

His passing transformed me from an angsty kid with the luxury of having a father and a heritage to resent, to a young person stricken by grief and longing. I made a vow to him, to my ancestors, that I would not forget my identity or origins in this land, in gurbet (غُرْبَة), where it would be so easy for me to do – to melt into whiteness and erase the truth of myself, my heritage. I dedicated myself to maintaining connection with my amcalar and halalar (paternal uncles and aunts) and their families, who sponsored my trips to Turkey during vacations from school. I poured myself into old Turkish music cassettes, music my cousins could not even identify, and relished visiting various türbe (shrines) in Adana and Hatay. I even attempted to learn Arabic on several occasions, as though learning this ancestral language would compensate for my lack of Turkish (to be fair Arabic classes are easier to come by in the US than Turkish classes).

These words are a continuation of my vow to him, to my ancestors. July 2019 marked 18 years since he left this realm, and yet I have never stopped learning from him. I am learning still about the bonds of family and love. My heart keeps thawing and melting. The first incarnation of this piece was written while I was living on Ohlone territory in the San Francisco Bay Area, and now I revise and edit it here in Adana*, in my father’s hometown. It has been 10 years since I last visited this land, 10 long difficult years fraught with illness, instability, transitions and growth in gurbet, my own self imposed exile of sorts.

Everything has changed, I now present as a man, and the last time I was here my kin saw me as a young woman. Before this physical trip, I participated in a psilocybin ceremony with friends. Through a slice in time, I conversed with my ancestors and reintroduced myself as İlhan, son of Cahit, son of Ali and asked for a journey of acceptance and love. And so it has been. Yes, everything has changed, and yet there is this timeless feeling still, as though I have been gone only for the space of one semester, like in old times. I was here, I am certain, all along, in the protective prayers of my uncles and aunts, in the anxiety of my cousins as they changed from children into adults, in the taste of thick coffee - with inquiries transformed into answers in the overturned cup. My heart was here all along.

* Final revisions made on Seminole land (Central Florida)