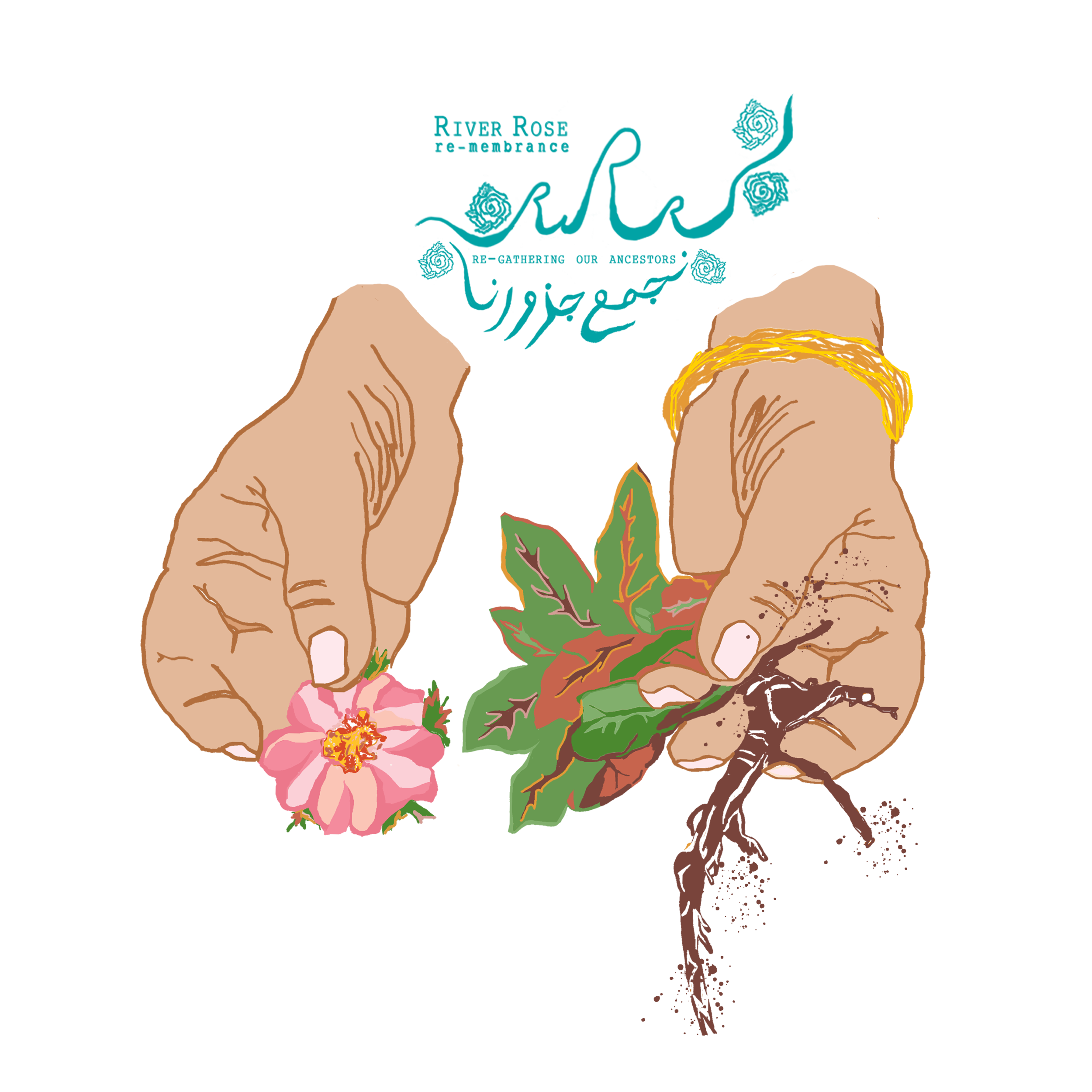

Roots of Exile : Thoughts on projection and longing for home

by Elizabeth -Isa- Knafo

The first time I watched the VHS tape was on a visit home a few years ago. Made in 1982, the film is called: Routes of Exile, A Moroccan Jewish Odyssey. It begins with the narrative of a removed spectator observing subjects like a conventional colonial ethnography. I have to watch in anticipation of what will make its way through the footage -- between the narrator’s lines. As a queer person I am practiced at finding meaning, thrill, and satisfaction between the lines of a book or a film. The movie continues with disconnected script: Amazigh are referred to as “Berber” over and over. An ordinary mistake that marks and dates the outsider position of the narrator. “Berber,” a slur that is also still vernacular, means something close to “Barbarian,” the actual word for this Indigenous Moroccan culture and people is Amazigh. The narration goes a little deeper, and describes Amazigh, Jewish, Arab, and African cultures creating Moroccan life. Speaking to these co-creative cultures that predate British, French, Spanish, European/ Ashkenazi Jewish and Israeli colonization projects is a simple truth and a potent undermining of more prevalent versions of history.

I’ve watched the film many times, for a while it was a kind of first date with new Moroccan jewish friends or acquaintances. Each time I watch, I vacillate between cringing and a sketchy validation and homecoming. Feelings that are mine to have but come with the disturbing anxiety around exoticizing my own heritage.

***

I catch feelings watching the grainy footage of souks, mellahs, and homes with people crowded around a table. Crowded and touching. Touching and talking over one another. This is a familiar family scene to me. In the film we move through homes and the streets. The archival footage casts deep associative nets, triggering anticipation that something I’ve been longing to know or have confirmed is imminent. It prompts reverie with shots of cooking, orchards, school houses, donkeys, wells, and tight alleys between stone structures. One scene depicts the Mimouna feast, the Moroccan celebration at the end of the spring holiday of Passover. This is a celebration that lifts up the shared and the common between neighbors while simultaneously recognizing the differing traditions among them. Before Passover, in order to prepare for the holiday, flour is stored at Muslim neighbors’ homes. On the final night, the Jewish neighbors retrieve the ingredients and create a feast of leaven desserts. This feast of sweets is prepared to be shared with open doors and all neighbors: Jewish, Muslim, Amazigh, Amazigh-Jewish, Arab-Jewish. The open house of desserts is in celebration the exodus from Biblical tales of bondage and escape through the desert with spreads of almond, pistachio, and honey-soaked pastries. This is described as a “living expression in the shared friendship and celebrations of Mimouna on the last night of Passover, symbolizing the shared end of the desert of injustice…”* Israel has tried to co-opt this holiday, but this holiday cannot actually be conceived of by adherents of Apartheid, it nullifies the entire premise of eating communal, honey soaked Moufleta.

***

The film takes me on a tour of a home I’ve never been to. At one point a voice speaks about the Moroccan-Jewish diaspora to come after world war two and the independence of Morocco: “Leaving made them Moroccan, the soil still on their shoes.” I recognize this. He doesn’t mention the intense European Israeli Anti-Arab propaganda that single-handedly drove this exodus.

***

I’ve been told that at a few months old I was brought to my grandparents’ apartment in Queens and my grandmother and her friends passed me around, ululating to welcome me. I return to that story as the piercing vocalization never fails to kick up a metallic dust in me, striking an internal register. It calls forth a place and a cultural depth I don’t fully live, somewhere beyond my extended family in New York City. It summons a tunnel out of here. It’s a projection, a temporal leap, a blessing, a binding spell, sometimes I fear, an all too shallow idea of home.

Mid-way through the film, an exasperated Maghrebi-Israeli immigrant curses Theodor Herzl (a major figure in the history of Zionism) and the racism of the Israeli state. People interviewed discuss the layers of colonization at work in both Morocco and Israel. How poor Jewish and Arab communities were pitted against one another by the French, by the European Jewish assimilationist group, the Alliance Israélite Universelle**, and eventually by the state of Israel. Over and over again, a mournful regret is repeated about Morocco, before, we never had these problems — “we lived in perfect accord with one another.” Though surely oversimplified by nostalgia, there is a resonant, fundamental truth in this shared memory.

Someone in the film remembers the people cooking in public ovens with “little rolls of bread and small pigeons” and “daily life in common in the same street…” Watching the movie, I look for a place to scry through my projections, longings, and dislocation. The mesmerization from the old footage offers a way through a diasporic, colonial scrap yard. I think of all the Moroccan pottery my father has given me over the years, instead of answering my questions of what life was like for him back home. I look at a crack in one and think of my own breaking points: some of my relatives like many post-holocaust, colonized Jews pick up the Zionist mantle, shaking their fists willingly, signing on to further centuries of dispossession, grief, and calamity. So many things can rob you of home.

***

During dinners at my Grandma and Aunt’s apartments in Queens, Moroccan Jewish culture remains expansive, brazen, loving, undefined, served over many courses of dinner and platters of small exquisite cookies, but never explained. When I ask my aunt or my dad questions about life there, they talk about life being easier, no, life being harder. The nuances are tucked away in the response. They’re keeping something from me. Maybe they’re keeping it from themselves too. New York City goes well with diaspora if you want to forget all that. From here, and now, always — longing, forgetting, longing. Like the disembodied poet says in the film: “Listen, study the silence.”

* Souffles-Anfas p.204-205

** The Alliance Israélite Universelle was founded in the late 19th century by assimilated European Jews to “civilize” Maghrebi and Mizrahi Jews. It operated by setting up schools in many SWANA areas with large Jewish populations. After WW2 it became a major force of Israeli settlement propoganda, attempting to erase various SWANA cultural traditions, and fabricating or exploting differences between Jewish and Muslim people of Iraq, Turkey, Morocco, and other SWANA countries that the AIU ran its schools in.

-——