Here in the diaspora, ritual woke us up to the ancestor's stories

What continually amazes me about my family and my parents especially, is the deep resilience expressed through them naturally in just being who they (and we) are. Despite immigration and the changes of over 3 decades of separation from their own native homeland and both sides of our extended families, the traditional rituals live on, without question, without second thought, and sometimes, without even the consciousness of why or what it all means. Life in the diaspora is amazing. I am empowered every time I get to witness and remember this, and how deeply the ancestors live on despite place and time.Today, on April 19th, 2014, the Easter traditions really set foot in my mother's kitchen. The past week has been a build up, as my parents observed holy week in preparation for the holiday on its way. In the Eastern traditions, Easter is by far the most significant holiday for OG Arab Christians (I use the term "Christians" generally in this context to include Eastern Orthodox Christians of all varieties, as well as Eastern Catholics, etc). And when I say OG, I MEAN OG. For my family and ancestors, Christianity did not come by way of colonization. Christianity is, in fact, indigenous to our region and people, and the un-Latinized nature of their traditions and church, in Aramaic language and all, reflect this quite clearly. This is not to say that Christianity in the East has not also been colonized, because surely it (and we) has (have), but there is a deep indigenous root beneath the lines of the old ways still practiced by many Christians in the region, and I am always grateful for the opportunity to learn and collect wisdom from my grandmothers and family, and listen deeply to unravel the ancient mysteries underneath all they share. The earliest of my ancestors always speak through them somewhere, even when they themselves do not realize.

Pistachio Rose Water Stuffing

So today, my mother initiated the making of m3amoul, the traditional celebratory food made for the sacred occasion of Easter in our region (and also made by Arab Muslims on their sacred Eid/holiday - a non-sect-specific traditional ritual food of our region). M3amoul is a delicious dessert, prepared with a crust of buttery semolina and 3 different stuffings- pistachio with rose water, walnuts with orange blossom water, and dates... (with a few of mama's secret spices packed in between, of course ;) ). They are stuffed and then put in three different shaped wood carved molds with beautiful designs and then baked. I took the opportunity to regard my mama's special recipe and learn from her gift for making traditional foods, which she is always looked to as a gifted hand by her community and family for. I asked questions while she kneaded dough, recorded her offerings for as long as she would let me, and then she finished the process off by tracing a cross of four directions in the dough to rise, "we ALWAYS put the cross in the dough, that is the reason we are making it," she emphasized, and we went on to collectively participate in the most laborious (and fun) part of the process with my cousin and sister- stuffing the cookies. As the old ways would have it, the women suddenly gathered near the kitchen, where all the real magic seems to happen. And something especially powerful happened today while we were doing this ritual. The act of it all made what sometimes feels like a removed and fragmented diaspora, feel whole and unified again. The resilience of ritual was really stirring in my mind, and then the ancestors... oh, the ancestors... I really witnessed the power of how they come thru in these moments of embodying these generationally old, simple but profound, acts of living in our cultural ways.First observation was simple, not only were all the women in the house suddenly present (which is rarely the case in the midst of busy day-to-day lives, and mind you, today was NOT the official holiday), but the 2014 amenities facilitated an even more dynamic village style fullness in the house, while my aunt, uncle, cousins, and grandmother were face-timing and calling all throughout our m3amoul making day. It suddenly was as though my whole maternal family was under one roof instead of cross country, watching my mother's working hands, making jokes, and telling stories. And THIS is what reinforced the space, I guess the ancestor's did not want to be left out, so they joined us to offer their stories for a good part of the ride...Have no doubts, being the story-keeper and family-history-seeker that I am, I have FREQUENTLY bombarded my mother (and every other elder in my family) with questions about the elders in our family, life in the village, our traditions, and more. And my mom, though loving and generous, can be sort of a rough-around-the-edges lady. She's tough, hella busy, and very practical. Close to 95% of the time, to my disappointment, she answers my seeking curiosity with "I don't know... I don't remember... Ask your aunt or grandma... Ask your uncle... Why is this important?...I don't have time... Stop bothering me!" or some simple one word answer. I am sadly, not really exaggerating. She's never been much of a story-keeper herself, and seems to slip in and out of clear memory, or at least the desire to share about her family recollections in Lebanon. I have asked her the same questions repeatedly on different days, in different places, different questions sometimes, all in the hopes that now and again I might catch her in a more sentimental or receptive mood, but to no avail. So, TODAY, I was shocked when the moment my mother sat down with us to start stuffing the m3amoul, and the drum like beat of our respective wooden molds being banged on the table to get the final buttery sweetness out, and the Turkish coffee was done brewing, and our chattering voices barely started crossing the table, she voluntarily started giving up stories, no questions needed. She spoke about my grandfather, reminisced on his hard working life and how Easter was his favorite holiday.

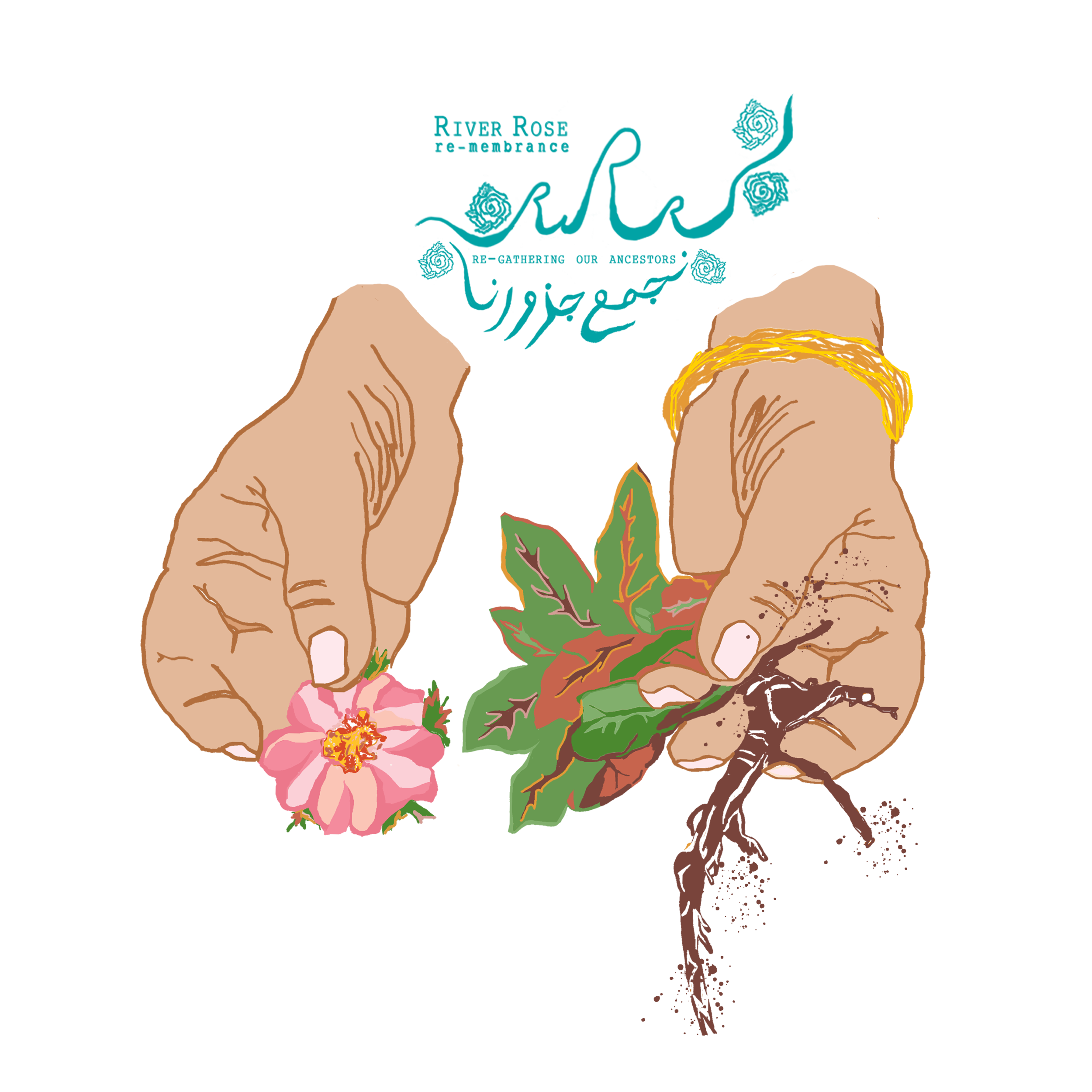

My mother’s working hands, and our wooden cookie mold/kitchen drum-beaters.

She spoke about my great-aunt and her life in the village, her spiritual inklings and her long hours of labor as a nanny to make ends meet, and she spoke of so much more. When my grandmother eventually got on the phone with us, my mother volunteered "wa jiddo kan yhakim kaman, ma hek?" "and grandpa used to doctor too (practice traditional means of medicine), right?" and they continued to share more and more. My jaw dropped, since literally 2 weeks ago I begged my mom to share SOMETHING, ANYTHING, about my Great Jiddo Aziz to me and she had less than a sentence to share. This particular piece of information surely would be of interest (and importance) to me, and an easy and obvious thing my mom could say, so I was a little surprised it had not escaped her before. My grandmother clarified the information, said it was mostly within the family that he practiced, and then went on to share some of her own plant medicine knowledge and asked me to send her some fresh olive leaves to keep balanced her blood sugar. My aunt told regional history, and recited Arabic poems, and on and on it all went...While on one hand, I was surprised (pleasantly), but a little flustered on why its so hard to get my mother to share this ancestral history she is holding which is so deeply important to me, on the other hand, I learned something so powerful through the context of this ritual and how the memories came about. I could see how boldly the ancestors became present, speaking through her memory suddenly so clearly and without effort. How her body was remembering, as she embodied this act which generations and generations of her ancestors and elders have done before her at this time of year, how the mere expression of this food preparing ritual, in its most simple diasporic form, was so deeply and fundamentally connected to what has happened before us, and how this so immediately softened her enough to open to it and be a vessel for its sharing.

Mama’s yummy m3amool <3

I was so grateful, especially since I actually haven't had the blessing of being home for easter for at least the past 3 years. The ritual lasted for hours, my aunts and uncles and grandmother chiming in with stories and pieces along the way, and my mother was glowing by the end of it. She even made more dough for another batch, despite long weeks and how tired I imagine she must have been to even start, she admitted to me, "I love to make m3amool", and I could see the peace on her face, the joy this ritual was bringing her especially with all of us there to join with her- the collectivity being a fundamental aspect of the tradition and ritual. I could see and experience how not only is this her traditional art, but its her medicine, and a powerful one indeed.