Berjouhi

Berjouhi

I arrive on this page with the memory of my paternal grandmother. Her name was Berjouhi. When she died, my aunt brought my cousins and I to her apartment to help clear it out. We each took a few of her belongings to remember her by. I took the large pink blanket that she kept in her bedroom, a box of old photographs from under her bed, and a tattered black purse that I had repaired but now sits in a closet in my mother’s house. When it was time to clear her kitchen, we found a bag of handmade mantuh in her freezer, which we cooked and ate promptly, in silence, then in laughter as we reminisced the time when my cousin walked in on her while she was getting dressed. She was wearing sheer pantyhose and her underwear peeked through the edges of the control-top and we all thought she looked damn sexy. My cousin told her so, and she pretended not to hear, went about her business. From what I could tell by looking at old photographs of her youth, she was all class, all business.

Her husband had a heart attack in his young age. She lived as a widow in Beirut and somehow found a way to care and provide for her multiple children in the midst of a fledgling civil war. In my recollection, she never tried to teach me how to cook or clean or perform any of the “traditional” duties that an Armenian woman is expected to take on/takes on with pride and relentless, meticulous skill. I learned how to do these things by observing my mothers and grandmothers tend to the daily minutiae of caregiving and managing their household, dusting, folding, making dolma, washing, washing, washing, pickling, jamming, scheduling, baking for us, baking for the church, baking for the school, baking for the neighbour’s grandmother who is in hospice care, making phone calls overseas so our connections to family and homeland are sustained, packing lunches and cleaning lunchboxes, driving me to and from ballet class, I can go on but this is not the time to write an encyclopedia of unpaid and unrecognized labor. They did all this on top of working and learning how to survive in a western diaspora, and processing the brunt of patriarchal violence that they experienced during the war and within their own families, (which is also work), for years, until I left home and began to do all that work for myself (inclusive of the home-work, survival-work, and healing-from-intergenerational-trauma work), although I wasn’t always good at it, but maybe I am better at it now.

I often think about how I am expected to be many things at once, expected by many people(s) and paradigms, always expected and not often accepted unless I am among others who suffer from the same diasporic dysphoria as I have come to know so intimately. How I have come to understand my own dysphoria as a person with diasporic lineage is directly correlated with the complex irreconcilability of my existence as both Armenian and born/raised-in-settler-environments, which is further complicated by my queerness. This experience often causes acute disorientation (and occasionally disassociation) within my own understanding of self, and also in relationship to place and with others. There are parts of me that feel most at home in Canada, and there are parts of me that feel most at home in Armenia. There are parts of me that feel at home in neither. Not often in both. I am aware that I am ultimately always both, and yet my experience of transitioning from being in Canada to being amongst my Armenian community or being in Armenia is always incredibly disorienting and painful. I can only describe it as being dropped into a new avatar. It is similar to when you have one of those dreams that feel like you’ve lived an entire lifetime and when you wake up, its as if you are being dropped into someone else’s body/life/time. Even though, and it is important to say this out loud, Armenia is not technically my ancestral homeland. It is surely the closest possible version of homeland, but my actual ancestors came from Sis, Melez Yozghat, Adana, Dikranagerd, Kharpert. These places are all found within the borders of Turkish land, where genocide continues today.

This is a discussion I wish I could have had with my grandmother Berjouhi, who I am told was a very clever woman, and for this reason, am sad that I don’t remember as much of her as I would have liked. I remember some. She loved to read. She valued education. She liked the piano. I think she would have loved my little one, Saana, because they are a good eater and they look like my father when he was their age.

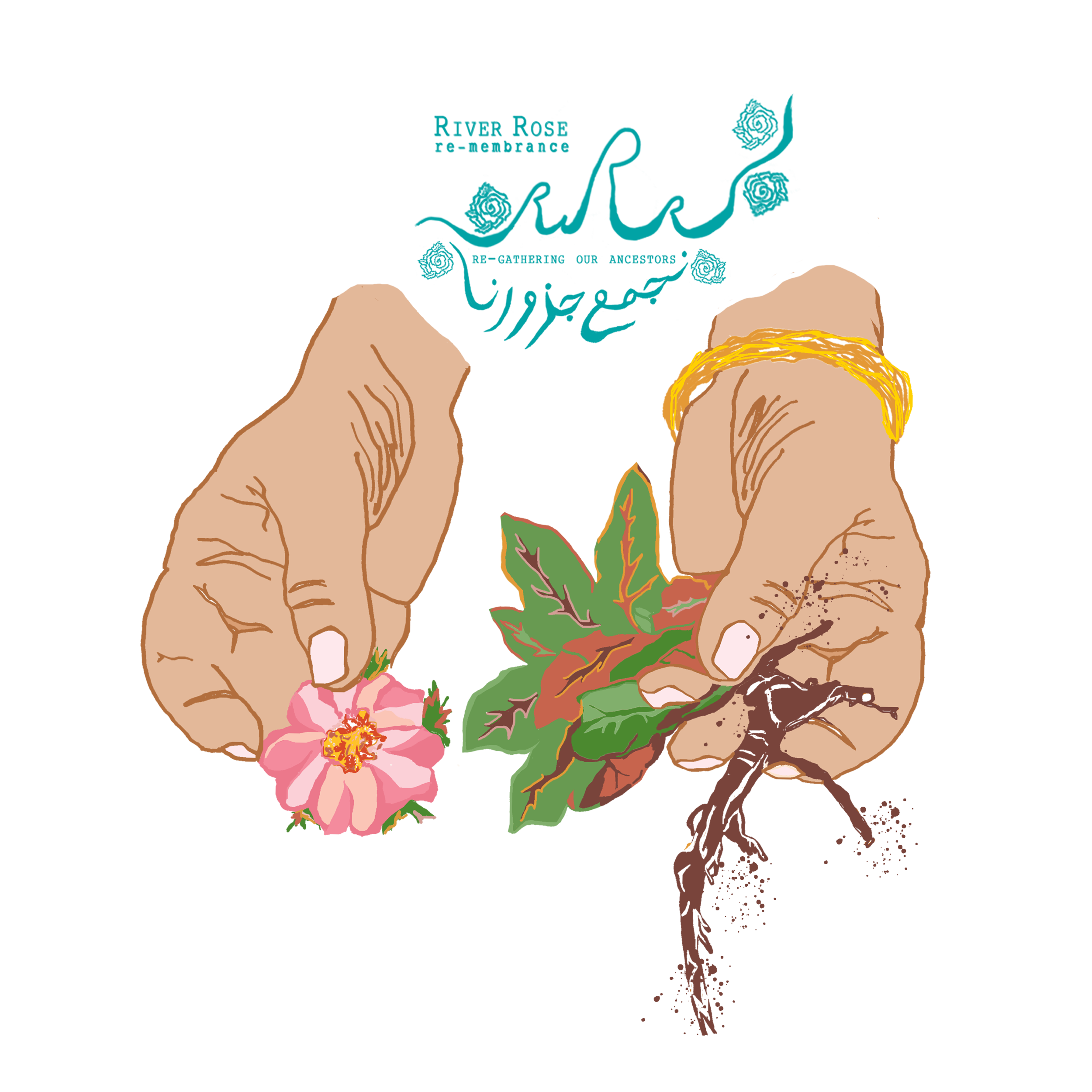

I do remember one time when I was no older than six, she braided my hair without much skill but with as much tenderness as a woman who deeply loved her kin, and mothered mostly sons, one of which she gave up for adoption to her own sister, a common practice at the time amongst families where one was not able to conceive themselves. It was a generous and painful act in my grandmother’s case because her sister was a woman who, much like many others at that time, but very much so, unlike my grandmother, believed in using one’s hands to discipline one’s child. And so she had to bear witness to this, among many other things, that I cannot begin to imagine were very difficult for her to endure, the worst of which may has been that she had to bury her own son, the one who was adopted, who ironically also died young and left a widow and child behind. I remember once after she had died, I fell asleep on an airplane and dreamt of her. I was crying one of those deep, cosmic cries. She held me and cried deeper, harder. She carried it with me. She was wearing a nightgown and we stood embracing one another in the middle of her apartment where she lived the last years of her life. I remember her nightgown, I remember the smell. All these things I know about her but my grandmother is still not someone that I knew very well, as she died before I had the sense to ask about how she lived and survived through so much grief and war and migration and, this woman, who was pulling knots out of my messy ballet bun while grazing my cheeks with the tips of her fingers, braiding my hair in the soft afternoon light diffused by lace curtains, was a woman whose ancestors lived through much worse, and I can only try to do right by them, to do more than survive, to thrive into the future with the support of my communities and fragments of dreams and learnings that I can muster.

--------

Kamee Abrahamian was born into an Armenian family displaced from the SWANA (southwest asian, north african) region, and grew up in an immigrant suburb of Toronto. They arrive in the world today as a queer and feminist mother, interdisciplinary creative, scholar, writer, producer, and facilitator. Their current home is traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee, adjacent to Wendat, and Anishnaabeg territories, and to the Mohawk community of Tyendinaga. Also known as Prince Edward County, Ontario.